but Lawsuites Agains Dotors Werein Fact Rare Until the Middle of the

MISSOURI STATE Athenaeum

Missouri's Dred Scott Case, 1846-1857

In its 1857 conclusion that stunned the nation, the United States Supreme Court upheld slavery in U.s.a. territories, denied the legality of black citizenship in America, and declared the Missouri Compromise to be unconstitutional. All of this was the issue of an April 1846 action when Dred Scott innocently made his mark with an "X," signing his petition in a pro forma freedom arrange, initiated under Missouri law, to sue for freedom in the St. Louis Circuit Court. Desiring freedom, his case instead became the lightning rod for exclusive bitterness and hostility that was only resolved past state of war.

Dred Scott

Credit: Missouri Historical Club

"Dred Scott, a man of color, respectfully states. he is claimed as a slave."

(Petition to Sue for Freedom, vi Apr 1846)

Initially, Scott's example for freedom was routine and relatively insignificant, like hundreds of others that passed through the St. Louis Excursion Court. The cases were immune considering a Missouri statute stated that any person, blackness or white, held in wrongful enslavement could sue for liberty. The petition that Dred Scott signed indicated the reasons he felt he was entitled to freedom. Scott's owner, Dr. John Emerson, was a United States Ground forces surgeon who traveled to various military posts in the costless land of Illinois and the costless Wisconsin Territory. Dred Scott traveled with him and, therefore, resided in areas where slavery was outlawed. Because of Missouri's long-continuing "once free, always costless" judicial standard in determining freedom suits, slaves who were taken to such areas were freed-even if they returned to the slave state of Missouri. Once the bonds of slavery were broken, they did not reattach.

Dred Scott was built-in to slave parents in Virginia erstwhile around the turn of the nineteenth century. His parents may have been the belongings of Peter Blow, or Blow may have purchased Scott at a later on appointment. The mystery of exact ownership is one that would follow Dred Scott, and after his family unit, throughout their lives as slaves. With few records extant, it is difficult to identify exactly when ownership of the family unit was transferred to various parties. Past 1830, Peter Accident had settled his family unit of four sons and three daughters and his 6 slaves in St. Louis. This was afterwards having moved from Virginia to Alabama, to attempt farming near Huntsville, and, when that failed, a movement from Alabama to Missouri. In St. Louis, Peter Blow undertook the running of a boarding house, the Jefferson Hotel. Within a year, though, his wife Elizabeth died and on June 23, 1832, Peter Blow passed away.

Front end view of St. Louis

Credit: Missouri Historical Society

The Blow children remained in St. Louis after the deaths of their parents and became well established in the city'due south guild through union to prominent families. Charlotte Taylor Blow married Joseph Charless, Jr., in November 1831; his male parent had established the first newspaper w of the Mississippi River and had been a leading opponent of slavery while editor. Charless, Jr., operated a wholesale drug and paint store, Charless & Visitor (later Charless, Accident, & Company when brothers-in-law Henry Taylor Blow and Taylor Accident became partners). Martha Ella Blow married chaser Charles Drake in 1835. Drake is better known in history for his role in the creation of Missouri's 1865 constitution. Every bit a leader of the Radical Republican Political party after the Civil War, he was determined to punish those considered Southern sympathizers; the constitution he helped author took away many of their rights, including enfranchisement. Peter Ethelrod Accident married Eugenie LaBeaume in 1833. She was from an sometime French cyberbanking family; her oldest blood brother was a wealthy businessman who, in partnership with Accident, formed Peter E. Accident & Company. She had two other brothers; i was the St. Louis Canton sheriff for a time in the 1840s, and one, Charles Edmund LaBeaume, was a St. Louis attorney who played an of import role in Dred Scott's freedom suits. All of these St. Louis connections proved helpful to Dred Scott.

".the said Dr. John Emerson purchased your petitioner."

(Petition to Sue for Freedom, 6 April 1846)

One of Dred Scott's ownership mysteries concerns the appointment of his sale to Dr. John Emerson. Information technology was erstwhile afterward the Blows arrived in St. Louis in 1830 and before Dr. Emerson reported to Fort Armstrong in Illinois on December 1, 1833. At that place is no extant record of the sale, although several theories have been posited. It is possible that Peter Blow sold Dred Scott to Emerson before his expiry. It is also possible that Blow's heirs sold him from the estate. On June 30, 1847, Henry Taylor Blow testified in Dred Scott's circuit court trial for freedom that Peter Blow sold Scott to Dr. Emerson. Emerson's attorneys did not object to this testimony or catechize Blow on its accuracy, so it is probable this is the manner in which the ownership of Dred Scott passed to Dr. Emerson.

John Emerson came to St. Louis onetime earlier August 1831. He served as a civilian doc at Jefferson Barracks for a fourth dimension before his October 25, 1833, appointment every bit an assistant surgeon in the United States Ground forces. He left St. Louis on November 19, accompanied by Dred Scott, to report for duty at Fort Armstrong, Illinois (the stay referred to in courtroom documents equally Stone Island). Emerson'south consignment lasted for nearly three years and, under the atmospheric condition of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, entitled Dred Scott to his freedom. That ordinance prohibited slavery in regions between the Mississippi and Ohio rivers and the Great Lakes, except every bit penalization for crimes. In addition, when the state of Illinois was created from role of the Northwest Ordinance territory in 1818, the country constitution prohibited slavery.

".and at that place kept petitioner to labor and service."

(Petition to Sue for Freedom, six April 1846)

Living at Stone Island was Dred Scott's first adventure to sue for his freedom, bold he knew he had that right. He did not sue, though, and in May 1836, traveled with Dr. Emerson to Fort Snelling when Emerson was transferred. Fort Snelling was located in the newly created Wisconsin Territory (role of the Iowa Territory afterward 1838), on the west bank of the Mississippi River. The journeying and residence at Fort Snelling was Dred Scott's second take chances to sue for freedom. Now he was resident in a territory that was governed by the 1820 Missouri Compromise, which prohibited slavery northward of 36° 30' except within the boundaries of the state of Missouri. Again, though, he did not pursue his opportunity to sue for freedom based on this residence.

Harriet Scott

Credit: Missouri Historical Social club

In either 1836 or 1837, Dred Scott married Harriet Robinson, a teen-anile slave endemic past Major Lawrence Taliaferro, Indian agent for the territory. Unusual for slave weddings was the fact that an actual civil ceremony took place. Taliaferro was a justice of the peace and performed the wedding. At some bespeak, ownership of Harriet was transferred to Emerson, although the record is unclear equally to how this came about-another buying mystery of the Scott family.

On October twenty, 1837, Emerson left Fort Snelling for assignment to St. Louis, which he had repeatedly requested. He traveled from the fort past canoe because the upper Mississippi River was already frozen and steamboats were not making the trip. Due to the mode of travel, he left backside most of his possessions, including Dred and Harriet Scott. The Scotts were left in the care of someone else, to be hired out until Emerson could brand arrangements to send for them. They had opportunity to escape slavery by running away in his absence, simply they did not. Nor did they endeavour to sue for their freedom during this time.

Almost immediately upon arriving in St. Louis, Emerson was transferred to Fort Jesup, Louisiana. He arrived there on Nov 22, 1837. The assignment lasted less than a twelvemonth, only during that fourth dimension in Louisiana he met Eliza Irene Sanford (known as Irene) of St. Louis; she was visiting her sister Mary, who was married to Captain Henry Bainbridge, also assigned to Fort Jesup at the time. Emerson married Irene on February six, 1838. In April 1838, at Emerson's asking, Dred and Harriet Scott traveled to Louisiana, thus voluntarily returning to a slave state. That September, the Emersons and the Scotts returned to St. Louis for a brief stay, and so traveled back to Fort Snelling in Oct. On that Oct trip back to Fort Snelling, Eliza Scott, named for her mistress, was born on the steamer Gipsey, captained by Thomas Gray, northward of the purlieus of 36° 30' , in free territory. The group remained at Fort Snelling until May 1840.

".Emerson was ordered to Florida. and left petitioner."

(Petition to Sue for Freedom, 6 Apr 1846)

On May 29, 1840, Emerson was transferred to Florida, where the Seminole War was existence fought. He left his wife and slaves in St. Louis, where Irene Emerson's father, Alexander Sanford, resided on his plantation, called California, in north St. Louis County; Sanford endemic four slaves. Dred and Harriet Scott were hired out to various people during that time. Emerson was honorably discharged from the United States Army in Baronial 1842. He returned to St. Louis simply, unable to maintain a successful individual practice in the city, settled permanently in Davenport, Iowa, on land he purchased in 1835. He began practice there in the summer of 1843. Irene Emerson joined him and gave birth to their daughter Henrietta in Nov 1843. On December 29, 1843, Emerson died suddenly; he was forty years old. The official cause of decease was listed as consumption, but it is possible he died of complications from syphilis. An inventory of his Iowa manor mentioned slaves, but the inventory is no longer extant, and then it is incommunicable to make up one's mind if this reference was to the Scott family. At that place is no mention of any slaves in Emerson'south Missouri estate inventory, although it is likely that Dred and Harriet Scott were living in or around St. Louis, hired out. Afterward Emerson's decease, Irene Emerson returned to St. Louis with her girl and lived with her father. His proslavery sentiments probably influenced many of her decisions afterwards Dred and Harriet Scott filed for freedom.

Past March 1846, Dred and Harriet Scott were hired out to Samuel Russell; he was the owner of a wholesale grocery, Russell & Bennett, located on Water Street in St. Louis. At some prior point, Dred Scott had been in the service of Irene Emerson'southward blood brother-in-constabulary, Captain Henry Bainbridge. Subsequently reports merits that he traveled with Bainbridge to Corpus Christi, Texas, but returned to St. Louis at the outbreak of the Mexican War. No mention of this travel is made in official courtroom documents. There is no mention of where Harriet and Eliza Scott were during the time that Dred Scott was with Bainbridge.

".He is entitled to his freedom."

(Petition to Sue for Freedom, 6 Apr 1846)

On April 6, 1846, Dred and Harriet Scott each filed separate petitions in suits against Irene Emerson in the St. Louis Circuit Court to obtain their freedom from slavery. These documents, identical in nature, stated that the petitioners were entitled to their liberty based on residences in the complimentary land of Illinois (Stone Isle) and the costless Wisconsin Territory (Fort Snelling).

The suits were brought under a Missouri statute that specifically allowed anyone held wrongfully in slavery to sue for their freedom. Specific procedures for filing suit were outlined in the statute. First, a petition to sue was filed in the circuit court. If the petition independent sufficient testify that the plaintiff was being wrongfully held, the judge ordered that the petitioner be immune to sue; security for all court costs that might be adjudged had to be presented to the court. The guess would also club that the petitioner have liberty to attend to counsel and court, and not be removed from the jurisdiction of the courtroom, or subjected to any severe penalisation considering of the liberty suit. Although proslavery in sentiment, Gauge John M. Krum approved the form of the petitions, which Dred and Harriet Scott signed with their marks, an "X," and granted them permission to sue.

"It shall be lawful for any person held in slavery to petition the general courtroom."

(Laws of the Territory of Louisiana, 27 June 1807)

The statute required that the action taken be an action of trespass for false imprisonment. It went on to crave that "The annunciation shall be in the common form of a announcement for false imprisonment, and shall contain an averment, that the plaintiff, before and at the fourth dimension of the committing of the grievances, was, and still is, a gratuitous person, and that the defendant held, and still holds, him in slavery." Clearly, Missouri police accommodated the pursuit of freedom under sure circumstances. As historian Don E. Fehrenbacher stated: "Anyone familiar with Missouri law could have told the Scotts that they had a potent example. Again and again, the highest court of the state had ruled that a master who took his slave to reside in a state or territory where slavery was prohibited thereby emancipated him" (Fehrenbacher 130).

Dred and Harriet Scott had no political motivation to pursue liberty. No one questioned their legitimate right to their liberty based on extended residence in free areas. That doubt had been resolved with the Missouri Supreme Courtroom'due south 1824 conclusion in Winny five. Whitesides, where a mandate of "once free, e'er free" became standard judicial exercise. Established legal precedents, however, no longer reflected what became an increasingly proslavery judicial mental attitude. From 1844 to 1846, xx-5 freedom suits had been filed in the St. Louis Circuit Court; only one resulted in freedom.

Dred and Harriet Scott's first attorney, in what became a long legal journey, was Francis B. Murdoch, who had moved to St. Louis from Alton, Illinois, in 1841. Murdoch was Alton's prosecuting attorney when abolitionist newspaperman Elijah Lovejoy was killed by a mob in that location in 1837. He may have connected with the Scott family unit through John R. Anderson who was minister of the Second African Baptist Church that Harriet Scott attended in St. Louis. Anderson had likewise lived in Alton; in fact, he had been Lovejoy's typesetter and was in Alton the night proslavery mobs destroyed the newspaper function and killed Lovejoy. Anderson returned to St. Louis soon later on and began helping slaves pursue their liberty whenever he could. There is no definitive evidence of the Murdoch-Anderson connection in assisting the Scott family. However, Murdoch did help the Scotts initiate their freedom suits, and posted the required security for them. For some reason, he moved to California in 1847 earlier their cases came to trial.

".at the office of Charles D. Drake. depositions will be taken."

(Notice to have Depositions, 10 May 1847)

Charles Drake

Credit: Missouri Historical Society

At this betoken, the Blow family, children of Dred Scott's former owner, became involved in the freedom suits, providing both financial and legal assistance. At that place are no known motivations for their involvement in the cases. The family may have felt some obligation to a quondam slave. It is probable that Charlotte Blow Charless, equally the family matriarch, requested her blood brother-in-law Charles Drake's assistance with Dred and Harriet Scott'southward liberty suits when Murdoch left. Drake was the widower of Martha Ella Accident and, after her expiry, his unmarried sister-in-law, Elizabeth Blow, cared for the ii young Drake children, keeping Drake in close contact with the Blow family. At this time, the future emancipator, described every bit intense and intelligent, supported slavery. It is not certain that Drake ever represented the Scotts in courtroom, but he did a thorough job of taking depositions and positioning the case for its St. Louis trial. He temporarily moved to Cincinnati, his family unit'southward dwelling, in June 1847, which over again left Dred and Harriet Scott without an attorney.

Again, there is no documentary evidence of how the Scotts' 3rd attorney became involved, but circumstantial facts reveal a possible scenario. Samuel Mansfield Bay, a New Yorker by birth, and quondam Missouri legislator and attorney general, became the attorney of record in June 1847. He was the attorney for the Bank of Missouri where Joseph Charless, Jr., husband of Charlotte Accident Charless, was an officeholder. Charless, Jr., signed every bit security for Dred Scott on legal documents. It is possible Charless asked Bay to go involved in the Scotts' freedom suits.

"Yous are hereby commanded, that setting aside all manner of excuse and filibuster,

you appear before our Circuit Court."

(Writ of Summons, 24 June 1847)

The example came to trial on June xxx, 1847, in the St. Louis excursion court. Estimate Alexander Hamilton presided over the trial. In a fortuitous turn of events, he had replaced the proslavery Gauge Krum; Hamilton'due south general sympathy toward slave freedom suits was favorable to Dred and Harriet Scott. George Goode represented Irene Emerson. Missouri law was conspicuously on the side of the Scott family unit. All Bay had to do was prove that Emerson had taken Dred Scott, and then Harriet, to reside on costless soil, making them complimentary by Missouri law, and that later Emerson'due south death, his widow claimed and held them as slaves in Missouri.

There were many precedents in Missouri police upholding the "once costless, always free" judicial practise. There was the cornerstone example of Winny v. Whitesides (1824), which held that a person held in slavery in Illinois then brought to Missouri was entitled to freedom based on that residence. That decision was followed just a few years afterward by Merry v. Tiffin & Menard (1827) which held that residence in any territory where slavery was prohibited by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 worked a slave's freedom. The validity of the Northwest Ordinance slavery prohibition was upheld by the Missouri Supreme Courtroom in their 1828 decision in LaGrange five. Chouteau and once again in Theoteste alias Catiche v. Chouteau (1829). That residence in Illinois worked a slave's liberty was upheld in numerous Courtroom decisions, including Julia 5. McKinney (1833) Nat v. Ruddle (1834) and Wilson v. Melvin (1837). The fact that Dr. Emerson was resident at a military machine post did not prevent emancipation, according to the Court's 1837 determination in Rachel v. Walker.Between 1837 and 1846, in that location were no new decisions made by the Missouri Supreme Courtroom to overturn the clearly-established doctrine of "once free, always free."

On the twenty-four hour period of the trial, Henry Taylor Accident testified that his male parent had sold Dred Scott to Dr. John Emerson. Witness depositions from both military posts established the fact that Dred and Harriet Scott had resided at the posts every bit slaves in service to Dr. Emerson. Catherine Anderson, the wife of a Fort Snelling officer, testified in her May 10, 1847, degradation that she had hired Harriet Scott for two or three months and stated that she knew others who had hired the Scotts while Dr. Emerson was stationed at Fort Jesup in Louisiana. Miles H. Clark, deposed on May thirteen, 1847, stated that while he was stationed at both Fort Armstrong (Stone Island) and Fort Snelling, he knew Emerson claimed Dred Scott as a slave and used him as such. Samuel Russell of St. Louis testified in court that he had hired Dred and Harriet Scott from Irene Emerson and paid her father, Alexander Sanford, for their services.

On cross-test, though, Goode revealed that Russell's wife Adeline had, in fact, fabricated the arrangements to hire Dred and Harriett from Irene Emerson; all Samuel Russell had done was pay money to Sanford. His testimony was dismissed as hearsay and did not evidence to the jury that Irene Emerson held the Scotts every bit slaves. Because of this technicality, the jury returned a verdict against the Scotts-they remained in slavery. At that place was no question at this point every bit to the validity of the Northwest Ordinance slavery prohibition, or the similar prohibition in the 1820 Missouri Compromise. The jury did non deny "once free, always free"-they simply did not hear testimony sufficient to prove that Irene Emerson claimed Dred and Harriet Scott equally her slaves. When Hamilton instructed the jury that Samuel Russell'south testimony was inadmissible, they returned a verdict for Emerson.

".the plaintiff. moves the Court to set aside the verdict rendered."

(Motility for New Trial, 30 June 1847)

Bay moved for a new trial, arguing that the Scott family should not remain in slavery because of a technicality in the legal proceedings that could be easily remedied. Hamilton granted a new trial in December 1847, but not before Goode filed a bill of exceptions to the motility for a new trial, resulting in the example existence taken on a writ of error to the Missouri Supreme Court; sitting were justices William Napton, William Scott, and Priestly H. McBride. A transcript of the circuit courtroom trial was filed in Jefferson City on March half-dozen, 1848. The case was argued on written briefs only; no oral statements were fabricated. At this point, Alexander P. Field and David N. Hall represented Dred Scott. Field was an adept trial lawyer and prominent effigy in Illinois and Wisconsin politics; little is known about Hall. Like Bay, the two attorneys had shared part infinite with Peter Eastward. Blow'southward brother-in-police, Charles Edmund LaBeaume.

Past the time the Missouri Supreme Court was prepared to hear the case on April 3, 1848, Judge Hamilton had already granted the new trial. Every bit a result, Gauge William Scott issued the unanimous decision on June 30, 1848, that there was "no final judgment upon which a writ of error can only lie," because the new trial had not taken identify even so. Again, there was no consideration of the political implications of slavery in the territories; the case was nonetheless just a suit for liberty, with the consequence still to be determined by St. Louis courts.

On March 17, 1848, before the side by side trial took identify, Irene Emerson had the sheriff of St. Louis County accept charge of the Scott family unit. He was responsible for their hiring out, and maintained the wages until such a fourth dimension as the outcome of the freedom suit was determined (custody of the Scott family unit would remain with the St. Louis County sheriff until March 18, 1857). Beginning in 1851, Charles Edmund LaBeaume hired Dred and Harriet Scott from the sheriff; they worked for him for the next seven years. Quondam in 1849 or 1850, Irene Emerson moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, and married Dr. Calvin C. Chaffee in Nov 1850. Chaffee, an abolitionist plain unaware of his wife's involvement in a slave liberty adapt, was elected to the United States Congress shortly later on his matrimony to Irene Emerson.

"If the jury believe from the prove."

(Jury Instructions, 1850)

St. Louis Courthouse

Credit: Missouri Historical Society

Although Hamilton had granted a new trial on December 2, 1847, there was a lengthy delay before it actually took place. First, the instance'due south detour to the Missouri Supreme Court took place in the spring and summertime of 1848. Upon its render to the St. Louis Circuit Court, it was docketed for February 27, 1849, but postponed because of a heavy court schedule. This happened again when a court engagement of May 2, 1849, was set. The possibility of a trial in late May was denied when a fire swept through St. Louis on May 17, bringing most business in the urban center to a complete halt. A cholera outbreak in the summertime delayed proceedings farther. The case was finally heard on January 12, 1850, with Estimate Alexander Hamilton presiding. The attorneys for Dred Scott were Field and Hall, who had represented him in the Missouri Supreme Courtroom. In 1849, Hugh Garland and Lyman D. Norris replaced Emerson attorney George Goode. Garland was a Virginian by nascence and had served in that state's legislature. Trivial is known about Norris' background, except that he was staunchly pro-slavery and never established a residence in St. Louis.

Field and Hall established the Scotts' residence in a free land and territory; at this point, at that place were still two separate cases, one for Dred Scott and one for Harriet Scott. The depositions of Catherine Anderson and Miles H. Clark were again presented. This time, though, a deposition of Adeline Russell was included, indicating that she fabricated arrangements with Irene Emerson to hire the slaves Dred and Harriet Scott. Samuel Russell appeared in court to testify that he paid for the hiring of the slaves. The technicality that had price liberty at the 1847 trial was at present rectified.

For their case, Garland and Norris claimed that Irene Emerson had every right to rent out her slaves. They stated that while Dr. Emerson was residing at Fort Armstrong (Rock Island) and Fort Snelling, he was under military jurisdiction-not the civil police that prohibited slavery in those areas. Armed forces law, they claimed, superceded civil constabulary and therefore Dred and Harriet Scott were not free. This statement of military machine and civil police force had already been presented to the Missouri Supreme Court in Rachel five. Walker (1837) and the Court determined at that fourth dimension that the statement did non use. Garland and Norris ignored this precedent, though, in an effort to protect Emerson's property interests.

With the new testimony from Adeline Russell proving that Irene Emerson claimed and held Dred and Harriet Scott as slaves, and with favorable instructions from Gauge Hamilton, the jury found for the plaintiffs. Dred Scott and his family unit were costless. Post-obit the procedures outlined by Missouri law, they won liberty just similar many other slaves had done previously in the country. The case was obviously not however the lightning rod in the fight over slavery politics that it later on became.

".the decision of the Supreme Court. shall also decide

and conclude the case of the said Harriet, his wife."

(Stipulation, 12 February 1850)

Emerson's attorneys immediately asked for a new trial, merely were overruled. They then appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court, which granted a hearing. It is posited that the justices were waiting for an opportunity to make a pro-slavery judicial pronouncement and Scott five. Emerson provided that chance. On February 12, 1850, an agreement was reached between all parties that but the instance of Dred Scott 5. Irene Emerson would be advanced; the upshot of that determination would utilise to Harriet Scott's instance, besides. The case was docketed for the March 1850 term in St. Louis. The justices deciding the instance were William Napton, who had been on the bench during Emerson's 1848 appeal, James H. Birch, and John F. Ryland.

At the Supreme Court level, Emerson'southward attorneys continued to maintain that military law was different from civil law when slave property was involved. They claimed this despite the Court's ruling to the contrary in Rachel v. Walker. Hugh Garland'due south brief, filed in March 1850, had ii points: one) consent of the master and 2) military jurisdiction. He claimed that because Emerson was ordered to the war machine posts, there was no implied consent on his part that he willingly took his slaves into free areas; therefore, residence in those areas did not work Dred Scott'south freedom. The Court had determined in Nat v. Ruddle (1834) that freedom existed only if the slave's residence in costless areas is with the master's consent. Garland followed up this argument with his claim that, to a certain extent, military machine jurisdiction annulled the slavery prohibitions of the Northwest Ordinance and the Missouri Compromise. He did not deny the constitutionality of those provisions; he simply stated they did non use in this instance.

David Hall prepared the brief for Dred Scott. He used the aforementioned arguments that he had promoted in the lower court: residence in a gratuitous country/territory worked the liberty of a slave and this was a solid judicial standard in Missouri. He claimed Rachel v. Walker denied the difference between military and civil law, and pointed out that when Dr. Emerson left Fort Snelling for Fort Jesup, he voluntarily left Dred Scott in a free territory, thereby working his liberty.

Because of an overloaded docket, the case was not taken up in the March 1850 term, but postponed until the October term. The decision of the justices to remand Dred Scott to slavery, though, had already been made. According to historian Walter Ehrlich, "For the showtime fourth dimension, politics was injected into the case, not by the parties, only by the judges of the Missouri Supreme Court in their intended decision" (Ehrlich 58). He states that the justices made a decision, in the midst of growing sectional tension over the expansion of slavery, to overturn all previous opinions that recognized the validity of slavery prohibitions. Napton and Birch were strongly pro-slavery. While his views were less resolute, Ryland could non be described every bit anti-slavery. Although the 3 reached a unanimous decision, their opinion was never written. Napton was to have formulated the written opinion, only postponed his writing while waiting for a particular legal tome to arrive in Jefferson City. Earlier the book arrived, though, the first opportunity for Missouri voters to elect their judicial officials arose in August 1851. Nine candidates ran in the contested election for the iii state Supreme Court seats; according to paper manufactures, the Dred Scott case as such was non a campaign topic. Napton and Birch were both voted off the bench in the Baronial 1851 elections.

"Times at present are not equally they were,

when the sometime decisions on this subject were made."

(Missouri Supreme Court Stance, filed 22 March 1852)

The case, then, came before a new Court comprised of two new justices, Hamilton Gamble, William Scott, and the one remaining justice, John Ryland. Hamilton Adventure, born in 1798 in Virginia, was a St. Louis attorney and Whig; he began legal exercise at the age of 18 and was appointed Missouri'south Secretary of Land in 1824. His legal technique was clear, cursory, and logical. William Scott was a pro-slavery Democrat who had been on the bench during Irene Emerson's appeal in 1848. The new Court met in St. Louis for the Oct 1851 term, where they examined the Dred Scott case. The election of the two new judges, though, did little to change the political motivation, already in play, for a pro-slavery decision.

In anticipation of the hearing, Alexander Field resubmitted the 1850 briefs to the court. Emerson'due south chaser, Lyman Norris, not aware of Field's action, was in the process of preparing a new brief for the Court's test. He obtained permission to file it late. His brief is of particular importance, says Ehrlich, considering it marked "a significant alter in the legal arguments" (Ehrlich 61). Although the justices questioned the validity of the slavery prohibitions outlined in the Ordinance of 1787 and the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Emerson's attorneys had never made validity of the prohibitions an argument in previous court appearances. In his new cursory, Norris did non say the prohibitions were unconstitutional, just he questioned them as legal principles in his challenge of "one time costless, always costless." His "sober second thoughts" on the matter challenged for the first time congressional prohibition of slavery in the territories. Dred Scott's adapt for freedom was no longer simply that-the questioning of congressional authority now turned the example into a lightning rod for the slavery controversy.

The Court adjourned on December 24, 1851, and reconvened on March 15, 1852. On March 22, 1852, they rendered their 2-ane decision reversing the lower court decision. Justice William Scott wrote the opinion, with Ryland concurring. Scott did non deny that freedom suits had been presented to the Court previously. He claimed, though, that the decisions in those cases were fabricated on the basis of the constitutions and laws of other states and/or territories without regard to the policies in Missouri. While recognizing that interstate comity could be a positive matter, he did non feel Missouri should have to recognize laws that were in opposition to its ain; there should be a limit to the acknowledgment of comity. Scott likewise did not deny that the Missouri Compromise slavery prohibition was valid; he merely felt information technology was only valid where it applied, which was not within the boundaries of the state of Missouri. He acknowledged the correct of slaves to obtain their liberty when taken to free states and/or territories; he advised, though, that slavery status reattached upon return to a slave land. The racist rhetoric that had surfaced in Norris' brief was besides credible in Scott'southward stance when, in his decision, he stated that slavery was the will of God and that "Times now are not as they were, when the onetime decisions on this field of study were made." With this statement, Scott all but admitted that racial and sectional prejudices influenced the decision.

In his dissenting opinion, Justice Hamilton Hazard also addressed the outcome of comity. He asserted, though, that the differences in achieving emancipation had always been honored amidst courts of dissimilar states and that taking a slave where the institution was expressly prohibited was a tacit act of emancipation. He cited cases from Missouri, Louisiana, Virginia, Mississippi, and Kentucky in his justification of the emancipation force of the 1787 Northwest Ordinance. In final, he acknowledged the irresolute times and the fact that the slavery issue was condign explosive in American politics and wrote, "Times may accept inverse, public feeling may accept inverse, simply principles have non and practice not alter, and in my judgment at that place tin can be no safe basis for judicial decisions, but in those principles which are immutable." Yet, Dred Scott was remanded to slavery.

On March 23, the mean solar day after the Missouri Supreme Court handed down its opinion, Irene Emerson Chaffee's attorneys appeared in the St. Louis Circuit Courtroom, filing an lodge for the bonds signed by the Blow family unit covering the court costs. The attorneys also requested a render of the slaves and the payment of the slaves' wages of four years (at 6% interest). Judge Alexander Hamilton denied the lodge; no caption for his ruling was made in the record books.

"This 24-hour interval come once again the parties by their attorneys."

(Official Court Record, 15 May 1854)

Roswell Field

Credit: Missouri Historical Club

Non satisfied with the Courtroom'southward determination, on Nov 2, 1853, Dred Scott'due south friends helped him institute a suit in the Circuit Court of the United States for the District of Missouri. The Blow family, though, had made a conclusion that it could no longer financially support the Scott family's pursuit of freedom, especially since the prevailing attitudes appeared to be hopelessly against such a matter. A new attorney represented Scott since David Hall had died in the spring of 1851, before the Missouri Supreme Court decision, and later on the decision, Alexander Field moved to Louisiana. Charles Edmund LaBeaume, who had been hiring the Scotts since 1851, consulted Roswell M. Field (no relation to Alexander Field) nearly the case. Field was friends with Alexander Hamilton and Hamilton Gamble, both of whom were sympathetic to the Scotts' cause. Field agreed to work on the case, free of charge, and suggested a conform in the federal courts under the diverse-citizenship clause, which governed lawsuits between parties who were residents of different states.

At this juncture in the case, Irene Emerson's brother, John Sanford, claimed ownership of the Scott family unit. This claim, like many Dred Scott ownership mysteries, has never been solved. There are no papers transferring buying to Sanford from Chaffee. The Scott family unit had ever been a sort of communal property to the Sanford family, so perhaps John Sanford, as an executor of his brother-in-law's estate, felt he was responsible for the slaves and, in a sense, their owner. Sanford was a West Signal graduate and wealthy businessman. Although he had previously resided in St. Louis, past 1853, he was living in New York City. He maintained family unit ties in St. Louis because of his 1832 marriage to Emilie Chouteau, girl of Pierre Chouteau, one of St. Louis' largest slave-holding families. Though she died in 1836, Sanford was already an agile partner in nearly of the Chouteau family's business interests. Afterward his wife's death, Sanford moved to New York as the eastern representative of the American Fur Visitor, acquired from John Jacob Astor. This necktie to Chouteau explains in part Sanford's desire to continue fighting against Dred Scott'southward pursuit of freedom. The Chouteau family were unyielding in their defense of the institution of slavery and had been involved in numerous liberty suits. It is probable the family, peculiarly Pierre Chouteau, encouraged Sanford to continue defending his property rights (or at least those of his sister).

Field's ultimate purpose in standing Dred Scott's cause was to obtain from the United States Supreme Court a final judicial settlement of 1 question: Did residence in a complimentary land or territory permanently free a slave? At issue was the Missouri Supreme Court's determination in Dred Scott'south case that Missouri law could remand to servitude a person who had been emancipated based on residence in a free state and/or territory. The search for the respond to this question brought other questions to the fore, such every bit, did a black person have the right to be a denizen of the United states of america and thus bring accommodate at all? These legal aspects of slavery interested Field, probably more than the moral and ethical issues. Field claimed that being a Negro of African descent did not bar anyone from citizenship or the right to sue. This was a subject area that Principal Justice Taney would address in his 1857 opinion.

The November 1853 arrange was similar in virtually respects to Dred Scott'south original plea of trespass against Irene Emerson in 1846. This time, though, the arrange mentioned his daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, and claimed damages of $9000. In April 1854, Sanford's attorney, Hugh Garland filed a plea in abatement, which challenged the court's jurisdiction claiming that Dred Scott was not a citizen because he was a "negro of African descent." Field filed a demurrer stating that this fact did not bar Scott from citizenship or the right to sue. Gauge Robert W. Wells upheld Field's demurrer. Considering the court claimed jurisdiction, Sanford pled not guilty to Dred Scott's charges.

Field and Garland prepared an "Agreed-Upon Statement of Facts" in 1854, which was essentially a biographical sketch of Dred Scott's life from the time he was purchased by John Emerson through the 1852 Missouri Supreme Courtroom decision. Historian Kenneth Kaufman speculates that this articulation argument "probably signaled the point at which Dred Scott'southward freedom no longer depended on proving residence on gratuitous soil, but rather on proving that liberty, one time gained on costless soil, could be retained upon return to slave territory" (Kaufman 187-188). No other witnesses or testimony were offered after the statement was read to the jury on May 15, 1854. The United States Excursion Courtroom constitute in favor of Sanford, leaving Dred Scott and his family in slavery. Field appealed to the United States Supreme Court at the December 1854 term. Interestingly enough, Judge Alexander Hamilton had already fabricated a notation regarding Dred Scott five. Irene Emerson in the tape books of the St. Louis Excursion Courtroom. Information technology read: "Continued by consent, waiting determination of U.S. Supreme Court." Hamilton fabricated this notation on January 25, 1854, many months earlier the federal court handed down its decision averse to Dred Scott. This notation suggests that those involved knew the case was headed to the United States Supreme Court, regardless of the outcome at the U.Southward. circuit court level (Kaufman 189).

"But no doubt he will find at the bar of the Supreme Court

some able and generous abet."

(St. Louis Daily Morning Herald, 18 May 1854)

The United States Supreme Court did non hear the case until February 1856. Roswell Field arranged for Montgomery Blair, a St. Louis attorney living in Washington D.C., to fence Dred Scott'south case before the Supreme Court. Considering the case was condign more than high profile in the bitter conflict over slavery, Field needed a high-contour lawyer to argue information technology before the Court.

The Blair family was politically influential in St. Louis and Washington, D.C. Though role of the Southern elite, they opposed slavery expansion. The family enjoyed a shut friendship with Missouri's long-time Us Senator Thomas Hart Benton and strongly identified with the pro-Benton faction in Missouri. Montgomery Blair was outspoken in his antislavery views and, with his blood brother Frank, had been a leader in Missouri's Free Soil Move. After consulting with his father, Francis Preston Blair, and securing a promise to underwrite the court costs from Gamaliel Bailey, editor of the anti-slavery "National Era," Blair agreed to represent Dred Scott.

John Sanford also had new representation in the United states of america Supreme Court. Hugh Garland died in October 1854; Lyman Norris had already left Missouri. Sanford acquired Reverdy Johnson, a nationally-known constitutional lawyer from Maryland, and Henry South. Geyer, St. Louis attorney and U.Southward. Senator for Missouri. Geyer, who defeated long-term Senator Thomas Hart Benton in 1850, represented a number of pro-slavery clients in Missouri, including Pierre Chouteau. Both Johnson and Geyer argued the case at no charge to Sanford.

In his brief filed February seven, 1856, Montgomery Blair argued that freedom based on residence in a free state or territory was permanent and slavery did not reattach upon render to a slave state. This had ever been the example in Missouri until the state Supreme Court decided to inject electric current political views into its 1852 majority opinion. He besides claimed that a Negro of African descent could be a citizen of the The states. Roswell Field and Blair hoped that the U.S. Supreme Court would uphold Missouri's long-standing legal precedent and laws regarding slave freedom and citizenship.

Oral arguments began on February xi, 1856, with Blair reiterating the points made in his cursory. Geyer and Johnson challenged the authority of Congress to brand the 1820 Missouri Compromise; they thus denied Dred Scott'due south correct to liberty. They did non question whether Dred Scott could lose freedom gained by living in a free territory. They questioned whether he was ever free in the first place, since their legal interpretation did not recognize the binding force of either the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 or the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

In May 1856, the justices chosen for the case to be reargued in December. At that time, George Ticknor Curtis, a Boston chaser, Whig, and brother of U.S. Supreme Courtroom Justice Benjamin Curtis, assisted Blair in arguing the ramble questions of the instance. A final decision was delivered on March 6, 1857. Eight of the 9 justices wrote divide opinions. Vii justices, primarily pro-Southern, followed individual lines of reasoning that led to a shared opinion that, past law, Dred Scott was still a slave. Master Justice Roger B. Taney wrote what is considered to be the majority stance.

".they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect."

(Opinion of the The states Supreme Court, six March 1857)

Roger B. Taney

Credit: Missouri Historical Society

Taney's "Opinion of the Court" stated that Negroes were not citizens of the United States and had no correct to bring suit in a federal court. In addition, Dred Scott had not get a free man as a consequence of his residence at Fort Snelling because the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional; Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in the federal territories. Furthermore, Dred Scott did not become gratuitous based on his residence at Fort Armstrong (Stone Island), because his condition, upon return to Missouri, depended upon Missouri police as adamant in Scott v. Emerson. Because Dred Scott was not costless nether either the provisions of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 or the 1820 Missouri Compromise, he was still a slave, not a citizen with the right to bring suit in the federal court system. According to Taney's stance, African Americans were "beings of an inferior society. then far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." (Kaufman 221). Taney returned the case to the circuit court with instructions to dismiss it for want of jurisdiction.

"Taylor Blow.acknowledges the execution by him

of a Deed of Emancipation to his slaves."

(Court Record, 26 May 1857)

In spite of the Us Supreme Court's decision that Dred Scott was a slave, he did finally receive his freedom. Irene Emerson'due south abolitionist second married man, Dr. Calvin Chaffee, now a Massachusetts congressman, plant out his married woman owned arguably the most famous slave in America in Feb 1857, just before long before the Court's determination. Unable to intervene in the case at that point, Chaffee suffered "disparaging commentary" in newspapers nationwide and on the flooring of Congress because of the seeming hypocrisy of his ardent abolitionist stance while being a slave possessor. Chaffee immediately transferred ownership of the Scott family to Taylor Accident in St. Louis; Missouri law only allowed a citizen of the state to emancipate a slave at that place. Irene Emerson Chaffee agreed to this buying transfer on the condition that she receive the wages the Scott family earned over the concluding seven years. The wages amounted to nearly $750. There is speculation that, in 1857, Dred and Harriet Scott were worth about $350 each on the slave market. Had Irene Emerson Chaffee sold them, her render may have been less than the total of their wages earned (Kaufman 226).

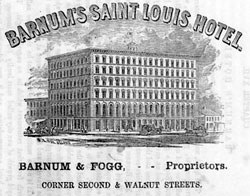

Barnum'southward Hotel

Credit: Missouri Historical Society

On May 26, 1857, Dred and Harriet Scott appeared in the St. Louis Excursion Court and were formally freed; Judge Alexander Hamilton approved the papers. Dred Scott took a job every bit a porter at Barnum's Hotel at Second and Walnut streets in St. Louis; he became a sort of glory in that location. The family lived off Carr Street in the metropolis, where Harriet took in laundry, which Scott delivered when he was not working at the hotel. Dred Scott did not live to savor his gratis status very long; on September 17, 1858, he died of tuberculosis. Their daughter, Lizzie Scott, married Wilson Madison of St. Louis, and had two sons, Harry and John Alexander. Harriet Scott died on June 17, 1876, at the home of Lizzie and Wilson Madison. She was buried June 20, 1876, in Section C of Greenwood Cemetery in St. Louis County.

"Sectionalism dead? Information technology was the nigh intense, biting,

overshadowing sectionalism that forced

this decree from the Supreme Court."

(New York Tribune, 21 March 1857)

Dred Scott tried to win his liberty at a time when white Americans were struggling to make up one's mind the political status of slavery, as well as their attitudes toward blackness people, slave or complimentary. He was simply in the wrong place at the incorrect time. The United States Supreme Courtroom's pro-slavery decision did not surprise the nation. In fact, information technology outraged much of the population when information technology was confirmed. When Emerson'due south attorneys questioned the constitutionality of the 1820 Missouri Compromise, they placed Dred Scott'southward case direct in the center of sectional political maelstrom. Extending slavery into the territories was a contentious issue with, equally the national media reported, oftentimes-violent reactions. The hostility and bloodshed of the Missouri-Kansas border troubles only emphasized the sectional chasm between northern and southern states over the slavery issue.

The United States Supreme Court was nether increasing pressure to offering a judicial resolution to the slavery issue. In denying Dred Scott his freedom, the Court made i of its most controversial decisions always. Waves of indignation swept the Northward. Editorial comments from northern newspapers immediately denounced the decision as wicked, detestable, and cowardly. Individual clergymen sermonized on the evils of a decision that dismissed an entire race as junior. The furor did not brainstorm or end, though, with the determination'south racism. Northerners who were non abolitionists, or even necessarily anti-slavery, protested the pro-Southern bias of the determination. Information technology allowed, virtually unchecked, the spread of slavery into territories and states, threatening the economic aspirations of free white laborers.

Taney intended the Court's determination to stop the slavery controversy for all fourth dimension. Instead, the intense and firsthand public reaction accelerated a concatenation of events that fabricated fighting a civil war unavoidable.

For farther reading:

-

Ehrlich, Walter. They Have No Rights: Dred Scott's Struggle for Freedom. Westport [CT]: Greenwood Press, 1979.

-

Fehrenbacher, Don East. Slavery, Police force, & Politics: The Dred Scott Case in Historical Perspective. New York: Oxford Academy Press, 1981.

-

Finkelman, Paul. Dred Scott 5. Sandford: A Cursory History with Documents. Boston: Bedford Books, 1997.

-

Kaufman, Kenneth C. Dred Scott's Advocate: A Biography of Roswell M. Field. Columbia [MO]: University of Missouri Press, 1996.

-

Konig, David Thomas. The Long Route to Dred Scott: Personhood and the Rule of Law in the Trial Court Records of St. Louis Slave Freedom Suits. UMKC Police Review 75,1 (Fall 2006).

Source: https://www.sos.mo.gov/archives/resources/africanamerican/scott/scott.asp

Postar um comentário for "but Lawsuites Agains Dotors Werein Fact Rare Until the Middle of the"